interviews

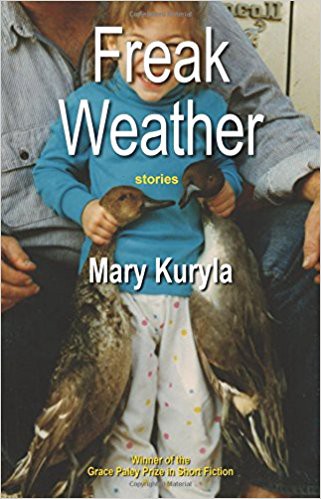

Mary Kuryla’s Characters Process Their Feelings Through Animals, Just Like You

A conversation with the ‘Freak Weather’ author about how hard it is to understand ourselves or each other without a crutch

The stories in Mary Kuryla’s Freak Weather are by turns disturbing and astonishing, blending the desire for a better life with the quicksand of situational reality. In each tender rendering, a female protagonist navigates her surroundings by protecting herself from the peril she’s trying to escape, often with an animal standing in as an ersatz totem for the issue. These tales twist until they become something undeniable, and Kuryla’s commitment to letting her characters make mistakes without pausing to consider their actions is something rarely seen in fiction. Despite the rush of end-of-semester grading, we were able to speak by phone about her characters’ attempts to understand their sexuality, themselves, and the people around them—and how they use pets as an emotional buffer.

Eric Farwell: In reading the stories, it becomes immediately clear that there’s something propelling them, and that being able to take whatever wonky motivations a character might have at face value is a big part of what makes the work unique. Where did this absurdist humor come from? Were you reading that served as a touchstone?

Mary Kuryla: I wasn’t necessarily reaching for humor, but I’d say that I find human nature funny, and the way we conceptualize our world does tend to contain a certain amount of humor. I think that all of the characters in Freak Weather Stories, to some degree, are underdogs. I gravitate to the underdog, but I’m not interested in portraying them as victims. I struggle with that as a woman and a feminist, because there was so much literature that was coming up for so long that felt concerned with women as disempowered. I’m not interested in telling those stories, because the approach doesn’t seem particularly literary, or even particularly empathetic. I’m more interested in how people get themselves tangled up, how their flaws create huge problems for them, and whether there’s a potential exit for them, a way to escape their own trappings. I guess that when I speak of the underdog, I’m interested in how these types of characters might succumb to that more easily compared to someone who has a lot of means to shore themselves up and protect themselves from such things.

In regard to the question of what I was reading, Denis Johnson’s Jesus’ Son, Tom Jones’s The Pugilist at Rest, and Barry Hannah’s Airships come to mind. So many of the stories in these collections endlessly portray men behaving badly. It’s interesting that in all this post-Vietnam writing, you have these men that are steeped in this bad behavior, but somehow our culture is really supportive or at least indulgent of this behavior. There’s something like a bad boy thing, and we sort of tuck into them. We might feel like their behavior is really shocking, but there’s something that really stays with us about the burden these men are under. I was really interested in telling a female version of that, because I just didn’t see any. I was interested in what it would be like to have a female character behaving really badly. Joanna Scott’s Various Antidotes stood out to me as having a really intense integrity about exploring women’s identity in a way that wasn’t always pleasing. Angela Carter’s stories of noncompliant and wayward women were also a source of inspiration, as were the films of women directors such as Agnes Varda and Chantal Ackerman.

EF: The biggest theme in the collection is the lack of understanding these characters have of themselves. Often, there’s a shift where a protagonist thinks they understand, but then loses their grip on that certainty. Perhaps more interesting is when you don’t try and posit a reason, but just put the job in the reader’s hands. For you, what holds fascination in regard to what we think we know about ourselves and how we come to different realizations?

MK: These characters always think they can outrun their feelings. We all do that to some extent. You might even observe this behavior in another person—when, say, you’re taking a walk with someone, and you bring up something unpleasant, that person will start walking faster. It’s just a simple thing we all do. Take a story in the collection like “The Worst of You,” where there’s a mom packing to go to jail for child neglect. I was trying to work with the thread of the psyche unspooling. You could almost say it’s a stream-of-consciousness piece, but it also leads to all this action, sets her on this path of what she’s going to go do, even if by the end she undoes it all. In some of the stories, I was working with how language itself can create momentum, how language can chase both towards and away from itself. Since my background is in filmmaking, and as someone steeped in the history of cinema, my work is at times influenced by experimental traditions in film; therefore, I’m always trying to find a balance between story and form. I feel like I have to offer the reader a story, some semblance of story, so that the form can be tolerated. If you’re willing to understand the language and the rules I’m setting out formally, it’s because you believe there’s a story there that’s going to deliver. Maybe it won’t deliver in ways that are terribly familiar, but there is a story. You can say we create stories to try and figure out who we are, but I also think we put ourselves through things to find that out. For example, Penny, the main character in the title story “Freak Weather,” knows she’s in a bad relationship, but she doesn’t have the tools to get out of it. She’s just going to act out as a means of finding a way out.

You can say we create stories to try and figure out who we are, but I also think we put ourselves through things to find that out.

EF: It’s funny that you mention that, because the title story starts you off down this journey of using animals as emotional buffers. In “Freak Weather,” “Deaf Dog,” and “In Our House,” you take the time to set up a kind of vague or serious concern, and then bring in a dog or puppy to kind of separate the protagonist from that issue. In other words, the animals are used to divide the subject from peril.

MK: You know, when I worked with Gordon Lish, he encouraged us to find our limit or wound that we keep going back to. For me, it was rabbits. I raised rabbits as a girl, and I took a lot of solace in pets. Often when I would bring home pets, I’d have to take them back. There must have been something in animals for me where I believed I could protect them, but where they also, you know, helped mitigate my feelings. So, I think you’re correct, but I also wanted to point out that there’s real danger in taking the idea too lightly. I mean, the story “To Skin a Rabbit” is genuinely disturbing for some. In the story, the protagonist is trying to cope with forces in her world she can’t master. So she takes control of what she can.

A Culture of Violence is a Culture of Shame

EF: Animals are also used as emotional stand-ins in stories like “Animal Control” and “Introduction to Feathers.” What’s interesting is that these stories are much more interior than those that use pets or creatures as buffers. I’m not sure if you make that distinction yourself, but I’m hoping you could maybe speak to how you made those calls in a general sense.

MK: I can say that I didn’t necessarily have any conscious awareness of that, that the stories would become more opaque and interiorized or externalized as they unfolded. However, some stories were a lot harder to solve than others. For example, “Animal Control” eluded me for seven years. I worked on it a lot, and got feedback in workshops that could help tame the hell out of it, but nothing that helped if I wanted to stay with a story that was just not easy to contain. It wasn’t until Tony Perez at Tin House suggested I check out this essay by Lucy Corin called “Material” that I started to figure out the story. In the essay, Lucy Corin says that your material is your material. If you want to get answers for what your work is, a sense of what the language is asking for, you have to go back to your material and let it tell you. I took “Animal Control” and put the story up on the wall. I studied it and tried to figure out what it was telling me. It’s a weird way of detaching from your work and analyzing it. I suddenly realized that I needed to get the animal control officer downstairs into the basement, which I had not been able to do before. I had resisted taking her down the stairs because going into the basement in search of an abducted child is what happens in a thriller or horror story. But that was what the story required and, thanks to Lucy Corin’s essay, I figured out how to do it on the story’s own terms. So, I guess what I would say in response to the role of animals in these stories, is that an animal is often a projection of a young protagonist, while for the adult female characters, if an animal figures, it is often as a substitute for a child.

EF: Miscommunication also weaves its way into these stories. Again though, there’s this desire to subvert the expectations of the protagonist. In “Mis-sayings,” the dancer assumes her inability to correctly pronounce or sound things out is the reason she’s having a hard time connecting with her partner, not the situation they’re in. When you’re drafting, do you view this as another layer of subterfuge, or does this aspect of your craft have a different purpose?

MK: I am always looking at how we don’t understand each other. How language eludes us. I’m married to a Russian immigrant. I find that in being married to somebody who has a second language, I’m consistently thrilled by our miscommunications and how antic language can be. But even after my husband’s command of English was pretty flawless, he still had a habit of blending English words. He would take two words that were not necessarily similar in meaning but that nevertheless sounded similar and make them into one word, an unintended neologism. It was always fun to figure out the two words he had amalgamated; even more fascinating was to figure out how he had intended the word to be used. So, to me, I don’t see language as a fixed thing. I see it as elusive, full of tricks, and I like that best about it.

I don’t see language as a fixed thing. I see it as elusive, full of tricks, and I like that best about it.

EF: That’s funny, because I was going to ask you about your use of language. In the stories, there are a lot of bent phrases like “his smile is all sly boots,” that read like sayings or a kind of slang, but dial up the language more than render a character as regionally authentic. So your answer here perfectly accounts for the play there.

MK: The only other thing I could tell you was that I was a terrible speller as a kid. One of the reasons I was such a bad speller is because any spelling of a word seemed just as interesting as the correct one. I think that’s how I feel about phrasing. That’s how I feel about errors. That’s how I feel about language. In fact, that stuff is more interesting to me — the mistakes, the misalignments, the confusion — because it liberates us from our comfortable space in relation to language; and they make language come alive. There has been a great deal out there recently about William Gass, since he just passed away; his whole commitment was to make language flesh. To make language a thing. I think mistakes open up a space for language to shift from representation to delivering the actual thing itself.

EF: I wanted to end by asking about how you approached understandings of power in these stories. Men in “Freak Weather,” “Mis-Sayings,” and “To Skin a Rabbit” all have an inherently ill-informed sense of their own power in relation to women. You pull this neat trick where you showcase that women placed in these unfortunate circumstances are in control, but for the most part, you use that showcase of power as a social lubricant. In this way, it kind of goes back to the idea of the buffer, where they’re using their sexuality in order to gain ground and avoid an awkward or dangerous situation.

MK: I suspect that this collection can disturb some people because the female characters in it cannot be boxed in. They are not behaving in ways that people feel comfortable with. In “Mis-sayings” the American guy that the Russian émigré has come to live with only wants to see her as a ballerina, but she was a stripper in Russia. This American won’t let her be seen in that way. So, there is a certain relief in being able to show herself for who she is to the kid who comes to buy drugs. I have a tendency in my stories to deploy a stand-in; for example, in “Freak Weather” Penny needs to have it out with her husband, but she instead has a strange and precarious confrontation with her husband’s boss.

13 Literary Takes on the Lives of Animals

With regards to this idea that the characters are using their sexuality in order to gain ground and avoid an awkward and dangerous situation, I think some of those tactics spring from my love of cinema. Recently, I taught a class on cinematic and televisual bodies. We were looking at the body in cinema, and how different bodies gain power through visualization, through representation, through taking up screen space or by surrendering it. Actresses like Mae West and Marlene Dietrich, and these sort of earlier figures in the motion picture industry, enjoyed an incredible amount of power with their sexuality, and actually also owned it. Mae West had her own production company. She took credit for discovering Cary Grant. She padded her hips and breasts to spotlight her sexuality, and was in control of it, and especially in control of the script and her sharp and clever tongue. I do feel that women can have a great deal of power in their sexuality, but as a feminist I also recognize that it is a slippery slope where women are easily made vulnerable by the very same thing. A number of the stories in the collection deliberately take up these tensions.